There have always been poor people, in every society and every time period. However, our treatment of those less fortunate has not always been exemplary. Sometimes a poor person might have had family or friends to help them out, but if not, a poor person might be dependent on the community for care, and their treatment would vary, depending on where and when they lived. If you had an ancestor who was in a poorhouse, you may want to learn more about what that meant and how to discover what might have caused them to be there. Read on for details.

The inspiration for poorhouses in the U.S. was the British system of workhouses. British church parishes were mostly able to help indigent members until, by the early 1600s, there were just too many poor families, unmarried women, and hordes of children needing help. Unable to keep up, the churches relied on the government for assistance, and the British parliament passed several laws requiring compliance with specific steps to receive financial assistance. The elderly and handicapped were separated from those who appeared to be able-bodied. Sick people went to hospitals; children were placed in orphanages, and those who were deemed "idle poor" were taken to workhouses, where they were destined to no longer be idle.

Conditions in workhouses were terrible. They were "bare bones facilities designed to make poverty seem even less attractive. In these facilities, poor people ate thrifty, unpalatable food, slept in crowded, often unsanitary conditions, and were put to work breaking stones, crushing bones, spinning cloth or doing domestic labor, among other jobs."

When colonists arrived in New England, they brought the concept of the workhouse with them. They also brought the prevailing attitude that poverty was self-induced and that poor people really had no rights. By 1660, Boston had a workhouse, meant for "dissolute and vagrant persons." New England towns conducted "pauper auctions," called vendues, where individuals and their families were auctioned to low bidders who agreed to provide room and board in exchange for labor. Rather like an indenture, this practice lasted into the early nineteenth century, by which time almost every large community in the U.S. had a poorhouse.

Probably the culmination of misguided treatment of those in need came in New York City in 1828, when they purchased Blackwell's Island (now Roosevelt's Island) and built almshouses for the poor and elderly, hospitals for poor and sick, a workhouse for the poor who were able to work, and a "lunatic asylum" for those who were poor and mentally ill. Then, they added a penitentiary to the island, throwing all sorts of people in need in one limited space.

The Civil War in the 1860s led to an increase in the numbers of elderly parents whose sons had died, widows, children without one or both parents, and incapacitated men, all of whom needed services. This led to government reform and new laws regulating how the needy were to be treated. Eventually, benevolent societies and other charities stepped up to provide better housing for those in need. Some of these early laws and reforms led directly to the foundation of the welfare system as we know it.

Finding Poorhouse Residents in the Census

Did you have an ancestor who suddenly disappeared? It might be that person was living in a poorhouse, orphanage, or other institution. The local poorhouse, like other institutions, was treated as an individual household, where the residents might be called "inmates."The superintendent or administrator was sometimes called a "keeper."

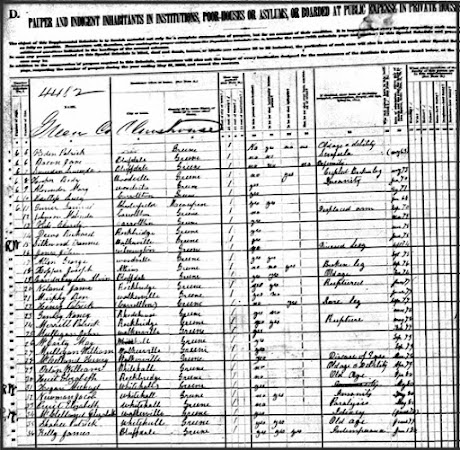

Here is the page for the poorhouse in Greene County, Illinois, Township 10, Range 11W in 1880. Note the enumerator called the residents "boarders" in this listing.

Interesting information, but if your ancestor was in a poorhouse at the time of the 1880 census, you should plan to check the special census taken that year for "Defective, Dependent, and Delinquent Classes." There were seven schedules with the following titles:

- [7-321]—For Insane

- [7-322]—For Idiots

- [7-323]—For Deaf-mutes

- [7-324]—For Blind

- [7-325]—For Homeless Children

- [7-326]—For Inhabitants in Prison

- [7-327]—For Paupers and Indigent Persons in Institutions

Individuals were entered first on the population census and then again on whichever supplement fit their condition. For a full explanation of how the supplemental censuses were taken, visit the United States Census Bureau website at https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial-census/technical-documentation/questionnaires/1880/1880-supp-special-instructions.html.

Here's what the supplemental census tells us about our Greene County poorhouse residents.

On this supplementary schedule, we discover that Patrick, our laborer, has old age debility. Jane, our housekeeper, suffered from scrofula, a form of tuberculosis that affects the lymph glands and causes abscesses, skin ulcers, and sinus drainage. Lucinda, who was bedridden, had "infirmity," so we really don't know much more about her. The list goes on with more detail about most of the residents, including Joseph, whose leg was actually broken, according to this.

This is the only census with this particular supplement, but other censuses do list poorhouse residents. The 1850 census has columns for physical and mental deficiencies, so be sure to look at those.

- The National Archives has microfilms of the 1880 supplements for Georgia, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Montana, Nebraska, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, Washington, D.C., and Washington State.

- Ancestry.com has the schedules for twenty-one states. Illinois is one of them, but Missouri is not included.

For More Information on Poorhouses

"Ancestors Fall on Hard Times? Check Out the Poorhouses!" by Nancy Maxwell, Grapevine Public Library Genealogy and Local History Blog, 25 March 2024, https://grapevinelibrary.info/2024/03/ancestors-fall-on-hard-times-check-out-the-poorhouses/

"The History of the Poorhouse," by Sarah K. Allen, undated, Primary Research: Local History, Closer to Home, https://primaryresearch.org/the-history-of-the-poorhouse/

"The Poorhouse," by Beverly Smith Vorpahl, Family Chronicle Magazine, January/February 2006, pgs. 21–24.

"Poorhouses and the Origins of the Public Old Age Home," by Michael B. Katz, pgs. 110 –140, Milbank Memorial Fund, https://www.milbank.org/wp-content/uploads/mq/volume-62/issue-01/62-1-Poorhouses-and-the-Origins-of-the-Public-Old-Age-Home.pdf

"Poorhouses Were Designed to Punish People for Their Poverty," by Erin Blakemore, latest update 30 June 2025, History Channel, https://www.history.com/articles/in-the-19th-century-the-last-place-you-wanted-to-go-was-the-poorhouse

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.